Over the summer of 2020, UCL researchers collaborated with the Victoria & Albert Museum of Childhood, artists and young people (11-14) to co-create a series of digital interactive creative studios. In this lecture, live streamed as part of UCL East’s Lunch Hour Lecture series, Dr Valerio Signorelli and Dr Leah Lovett from Bartlett CASA’s Connected Environments and Helena Rice, Senior Creative Producer at the V&A Museum of Childhood discuss how the RE-Invent Digital Pilot developed as a means of creatively engaging young people during an extended period of school and museum closure.

Here, the project team addresses some of the questions that were posted during the lecture by the live audience.

Q1: Did you have a clear sense of project goals from the outset, or did these only develop through the collaboration with artists and young people?

Leah & Valerio: We were approached by the V&A Museum of Childhood in January 2020 about presenting our research as part of the RE-Invent Festival planned for May. We’d worked with them on previous projects, such as Playing the Archive, and were keen to build on the existing partnership. The festival was going to be hosted in the Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green, and was planned to mark the renovation and transformation of the museum. We had proposed to create a digital ‘time capsule’ with audiences in Minecraft.

With the announcement of lockdown in March, the festival was cancelled. We’d already secured funding for the event from UCL Engagement, who manage a scheme to support relationships with East London partners ahead of the opening of UCL East. They encouraged us to explore different ways of delivering the project online.

We began speaking with Helena about how we might reimagine our proposal in response to the changing situation, as a way to support the museum, festival artists and young people with limited creative opportunities in lockdown. The idea for RE-Invent Digital emerged as an answer to this question.

At the outset, we knew we wanted to engage three artists to co-create digital commissions with young people (11-14). As researchers, we were curious about the potential for using open source, Web-XRR tools to ‘reinvent’ the museum as a collaborative, creative space. We wanted to make an interactive app. What that might mean in practice – how the young people might inform the art commissions, what kinds of creative activity the app should enable – these were negotiated through the collaborative process.

Helena: We hoped, through this project, to deepen our understanding of 11-14-year olds as a target audience for the new museum through testing co-creation processes via a digital platform. We wanted this space to provide opportunities for collaboration with artists, designers and museum professionals, in a time when engaging in our space was not possible. The artists that we commissioned for the project – Kristi Minchin, Dan Mayfield of School of Noise and Marawa Ibrahim – were approached initially for the festival and then for this pilot, because their practices reflect the ambitions of the new galleries, PLAY, IMAGINE and DESIGN. We wanted an experimental space in which to understand issues that might arise when developing content for the new museum and its learning programmes digitally with this audience. Facilitating workshops with young people on zoom was new for us, as was creating a digital creative tool. At the Museum of Childhood, the first lockdown and our distance from the museum itself, provided an opportunity to focus on an audience who hadn’t historically been attracted to the building and its collection- this provided an opportunity to forge new connections with local youth partners and create a group of young ambassadors to inform our work over the next few years of transformation.

The School of Noise led young people from Spotlight in a Foley Sound workshop. Image courtesy Dan Mayfield.

Q2: Could you talk a bit more on the restrictions and (maybe) advantages of online workshops via zoom? Could you share how you achieve collective “iterative design” through well-organization? How will you address the drawbacks in the future?

Leah: One of the main difficulties of workshop facilitation via Zoom is maintaining the momentum, keeping the ideas circulating. Zoom is set up to enable people to speak and listen. It privileges verbal forms of interaction. Working with young people and artists on a co-creation project, we wanted to explore different modes of communication – sculptural forms, for instance, and movement.

The artists had to adapt activities to accommodate the screen. At one point, Marawa invited us to stand up and follow the sequence of stretches that make up the Korean National Exercise routine. We finished up by taking off our shoes and socks and stretching our toes in front of our cameras. It was very funny, but it also revealed how the screen operates to restrict bodily movements. The body is still there, but it’s constrained.

In earlier sessions, there were times when the young people were outnumbered by adult collaborators and facilitators, which may have made it more difficult for them to speak up. We came around to the use of facilitated break out rooms as a way of giving the young people and artists space to think together and be creative. After a session, the group reconvened to share any outcomes. At the same time, we found that young people who were perhaps less confident being on screen and contributing verbally felt more able to share their ideas via the chat function. In that sense, the platform helped facilitate differing styles of engagement.

Helena: Sharing plans across the group ahead of sessions was key for ensuring engagement for those with limited bandwidth or device access. We did this via the youth workers, whose efforts supported attendance- not a given in this global context. De-briefing meetings and sharing of notes were more important than ever as the full team of all artists, young people and collaborators were never in the same zoom call at any one time. Sharing feedback immediately after each session also helped us to reduce the risk of constructing a dominant language for the project and its ‘design process’. We kept a working digital scrap-book, which we added to after each session and shared back with the young ambassadors and youth workers. This felt crucial to not only hold on to what we had done, but also to keep everyone informed of the project as a whole, with many moving pieces. This journaling process gave a narrative thread that was not, perhaps, reflective of the messy and sometimes incoherent experiences of co-creation. It did, though, help us make sense of these experiences in ways that ultimately fed into the development of the app. The visual document also increased access for a multi-disciplinary, intergenerational team, including professionals and children across time zones.

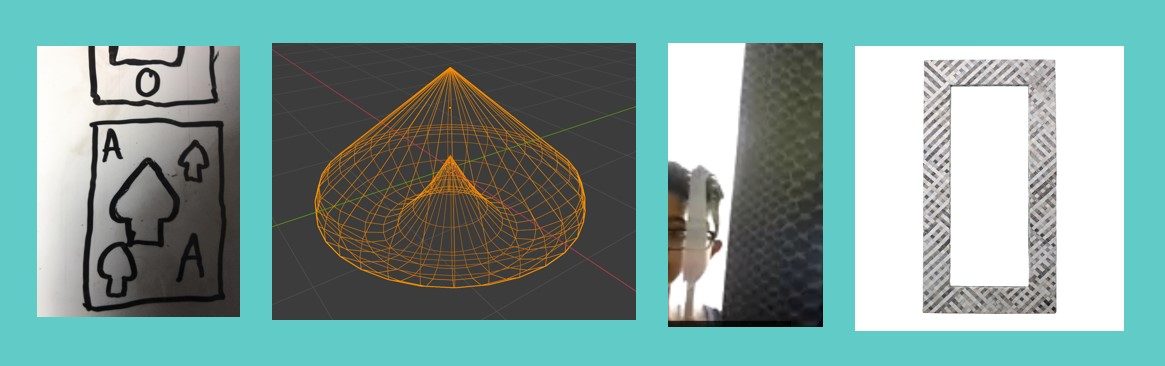

Kristi Minchin created 3d models in Blender using forms and textures chosen by the young people. Images courtesy Kristi Minchin and Leaders in Community.

Q3: I loved hearing about the traditions of engaged practice this grew out of – I’d love to know more about how you all started working in this area?

Leah: I got involved in an arts collective as an undergraduate student at art school in Edinburgh in the early 2000s. A group of us made promenade performances that played out across the city, transforming our rented apartments into elaborate stage sets, with bread dough floors and pencil drawings scrawled across the walls. We were a landlord’s worst nightmare, but it was exciting and it taught me a lot about the messiness of collaboration and how ambitious projects can happen when you pull together. After that, I became increasingly fascinated by histories of interventionism and social engagement in arts practices, and how they have been variously mobilised in different spatial and political contexts. My PhD investigated theatre director Augusto Boal’s development of Invisible Theatre as a means of enacting spatial justice during the Brazilian military regime (1964-1985). I don’t necessarily subscribe to his Theatre of the Oppressed method, but that practice-research project ultimately led me to explore more open-ended and connective modes of art-making. The Social Arts Network and the Design Justice Network are two great places to start for anyone interested in this area of practice.

Helena: I trained as a theatre maker and have worked in participatory theatre for many years. Like Leah, the work of Augusto Boal has informed my practice across settings and audiences. My engagement work has emerged from a bodily, somatic practice, so my focus has been on bringing awareness of the body into the space and centering movement as a form of communication. My role at V&A Museum of Childhood for the next few years is about engaging audiences in transforming the museum to be a space for creativity and design for children. Co-creation and co-production with children, schools and families has and will continue to inform design decisions and programming, and finding creative ways to do this remotely has shifted my engaged practice into a new area. I have learnt a huge amount on the possibilities and limitations of digital co-creation, and I am still considering how multiple and diverse forms of communication can flourish in it.

Valerio: Public engagement practice is a relatively new area for me. In a more general context, my background in architecture, and more specifically my research interests in the urban sensory studies have always put me in direct communication with different audiences, outside academia. Part of my research works intrinsically requires public participation, however, not always in the form of public engagement activities or knowledge exchange. These experiences have been an opportunity to me to explore new means, devices and interfaces, often borrowed from disciplines other than architecture and urban studies, to communicate, but more importantly, to enrich my research. I would consider the Playing the Archive project as the first research activities that led me to question the mutual interaction and positive impacts between my research and the public engagement activities and knowledge exchange.

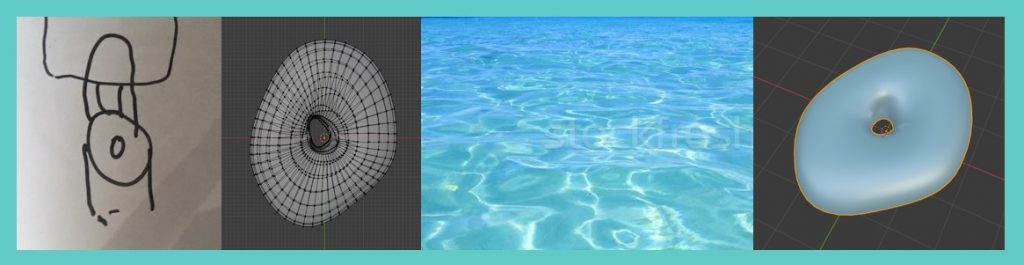

Screenshot of the RE-Invent Digital sound studio, created by CASA researchers, creative producers from the V&A Museum of Childhood, the School of Noise and young people from Spotlight.

Q4: Did you have to find any work-arounds for individuals who didn’t have suitable technology to participate? Have you considered longer term challenges in this area?

Leah: We were initially concerned about the young people having limited access to devices and data, and we discussed options for loaning equipment, but actually we didn’t find that to be a particular issue during the project. This may be partly because the youth organisations, Spotlight and LiC, were in a position to support access across their programme delivery. We were also blown away by the digital literacy of the young people involved in the project, and their familiarity with quite complex concepts and techniques.

We are aware that digital access is a big issue more generally. Part of the way this has been addressed through the project is through the use of web-based tools that enable accessibility across different devices and operating systems. The app was optimised for phone rather than laptop, as that is how most of our participants joined the sessions. Ultimately, though, the app does require web access.

Helena: I would write up all session activities and share with participants just before the workshops started. This enabled those who weren’t able to attend or access sufficient wifi for the zoom call to contribute their ideas and creations that then contributed to the build of the app. We found some participants who missed sessions, still felt empowered and enabled to share content that then formed digital assets and ideas in each studio.