Yaman Rawas Kalaji reflects on his learning experience in the Connected Environments Lab.

I was excited to start my new experience on the Connected Environments course at UCL. I wanted so much to design real-world systems that affect people’s lives, and this is the reason why I joined this programme in the first place.

In our first official project, we were asked to work on designing a simple plant monitor. One may think that this is too easy – what can we learn from a simple project like that? We started with a basic version of a plant monitor and were told to go further in customising it as we want. This is when things got interesting. Although we were around 15 people, almost no one came up with the same customisation as others. Each plant monitor was completely different, and each holds a different story.

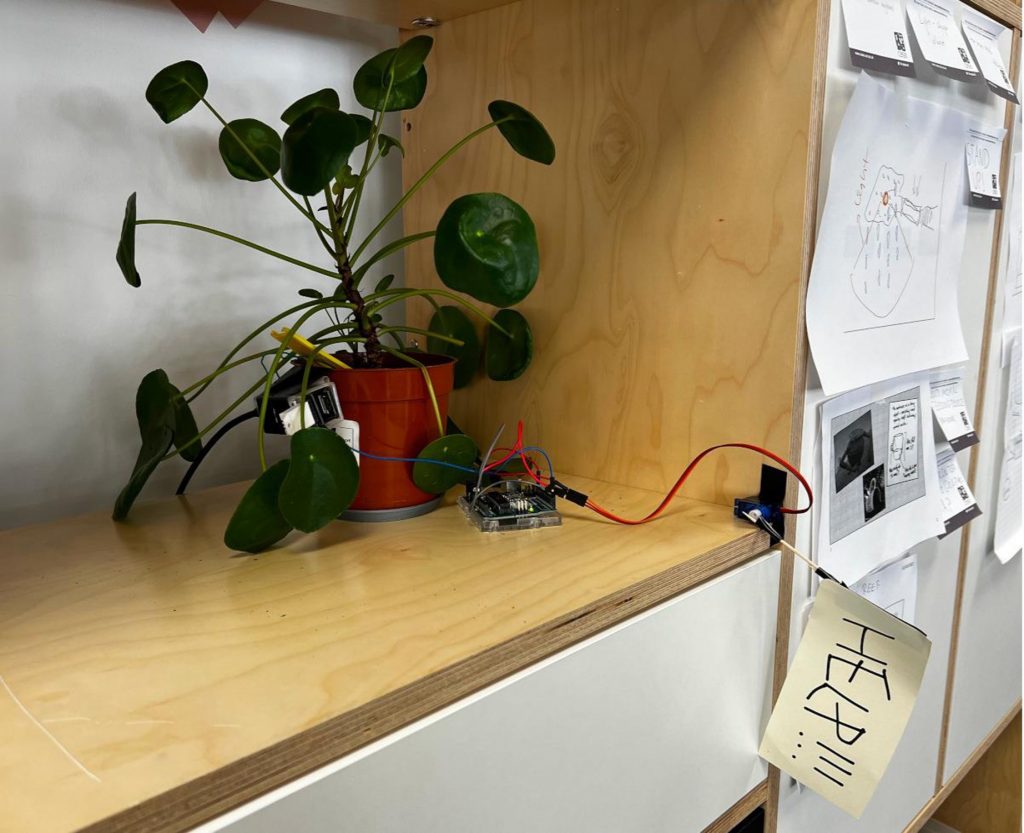

The following plant monitors are examples of creative ways to make plants interact with humans. This plant could raise a flag to tell you when it needs water (monitor by Jack)

jacks plant

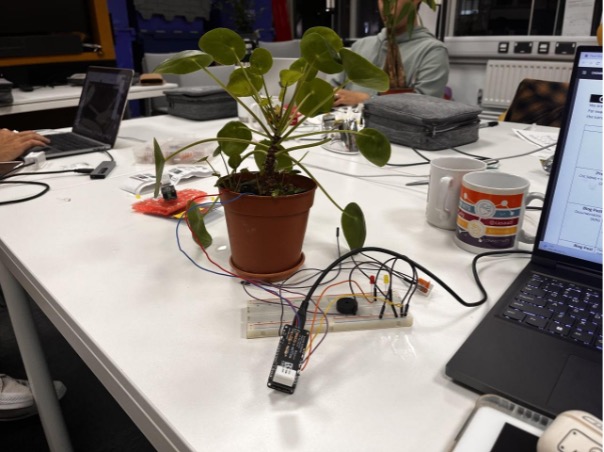

Other projects used a different incentive, such as Xiaoya’s, which made the plant play music depending on its situation.

xiaoyas plant

A buzzer connected to the plant plays different tones according to plant’s health status.

Although all of us had the same exact data, read from similar sensors, each person made their plant interact with surrounding environment in a different way. This was the first lesson I learned from this simple project; there are multiple ways to interpret and show the data to the real world.

While researching ideas to customise my plant monitor, I was inspired by an episode from the famous British TV series, Doctor Who, in which robots communicate using emojis. I thought this expresses a unique way to convey feelings, exactly as we use them in our daily chats to let people feel more than what we can say in words.

This level of interaction between users and technology is new in the last two decades. Users can now form a relationship with things using technology, and grasp a different meaning of what things usually represent. This what lead me to my project, Plantemoji.

What is Plantemoji?

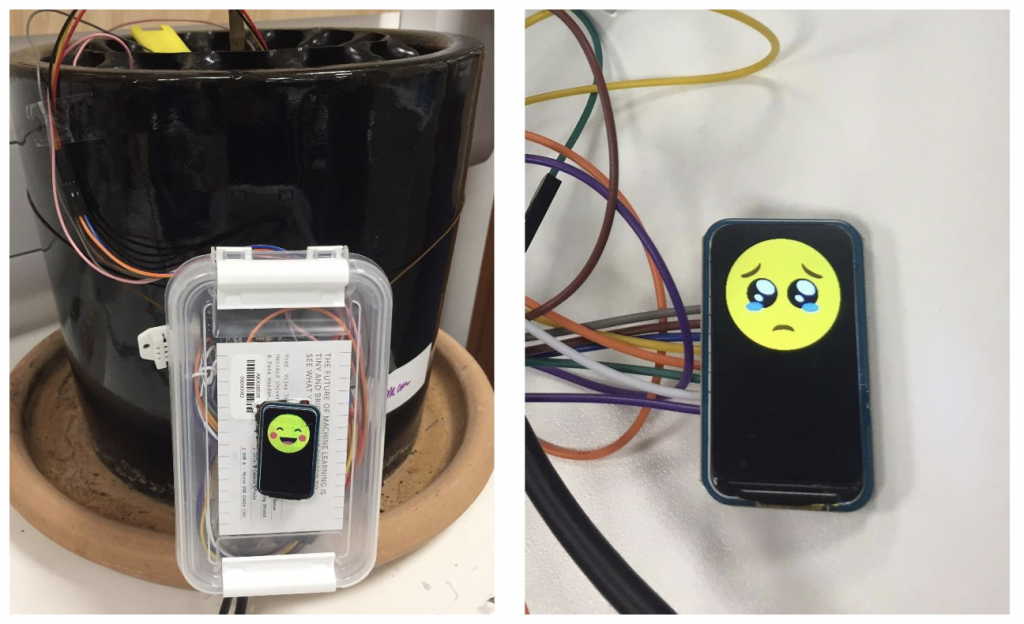

Plantemoji is a simple electronic device that can translate plant’s status into meaningful emojis displayed on a screen attached to the plant container.

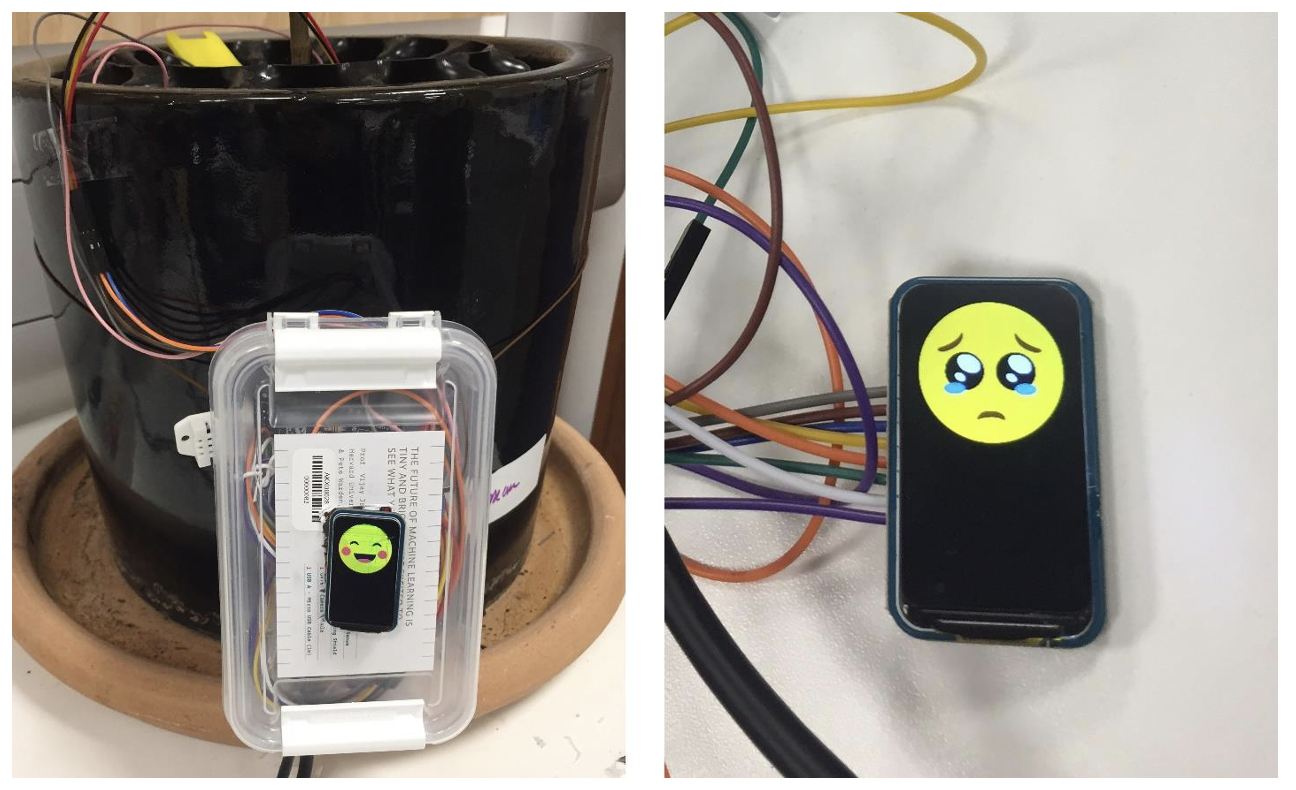

plant emoji

We were given a basic plant monitor, which uses nails to measure soil moisture, and has a temperature and humidity sensors. To this, I added two new extensions: the screen to display emojis; and a new capacitor soil sensor to compare between the two types of sensors. My objective was to observe how different sensors can measure the same environment, and how that affects our trust in technology.

Design process

An overview of Plantemoji project

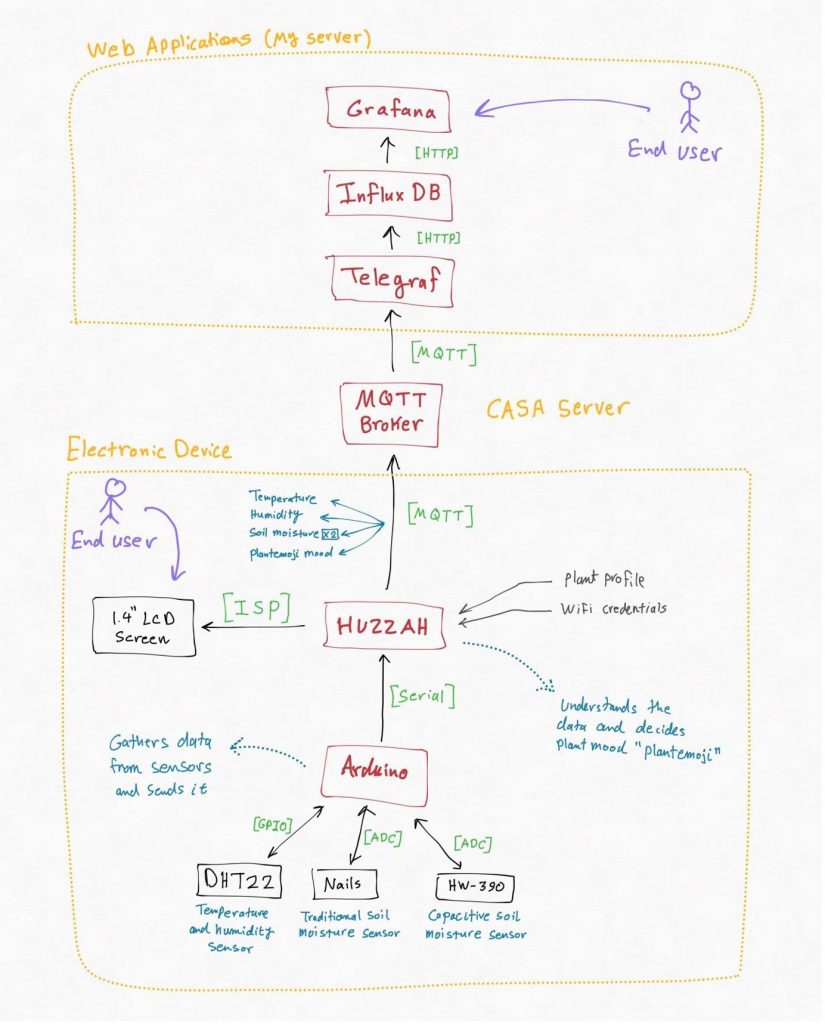

Plantemoji incorporates three sensors: a traditional soil moisture sensor, a capacitive soil mosture sensor, and a temperature and humidity sensor. I used an Arduino to add new sensors to the plant monitor, as Arduino has more analogue inputs compared with Huzzah (full electronic parts available in the Github repository).

The first sensor is the traditional nails moisture sensor, which measures the resistance between two iron nails inserted into the soil. This resistance translates into how much the soil is wet (more water means less resistance). I used CASA’s easy-to-use shield for this sensor. The second sensor is capacitive, and measures the resistance between two points (more water causes less resistance). The third sensor is the well-known DH22, which measures humidity and temperature.

The Arduino reads values from the 3 sensors and sends it to Huzzah using Serial communication. Huzzah, in turn, interprets those values to display the right emoji on the LCD screen, and sends those readings to my server in the cloud using MQTT.

Due to some difficulties, I decided to setup my own server which contains Grafana and InfluxDB, which are contained using Docker (details available on Github).

I reused the Arduino plastic case as an enclosure for Plantemoji. This allows better protection from moisture, and keeps the monitor compact and easy to be used during the next 9 months.

Plantemoji case

Enlightening results!

The usage of different sensors at the same time, and different setups for the same sensor, gave me a new perspective on how sensors work in the real world. It’s not only about reading values, since the conditions and setup environments can sometimes change the picture entirely! For example, testing nails in different conditions (corroded and good) returned different results. The same thing applies for nail depth inside the soil. The capacitive sensor has only one variable that affected its values, which was also the depth in soil.

Are sensor readings the only interesting results in this project? Of course not!

I was also observing humans’ interaction at the same time. Having a screen in my plant monitor visible to my colleagues at all times was really interesting. I received a lot of comments, some of which I didn’t expect:

“I see your plant is happy today!”

“Why did you make your plant sad?”

“That’s adorable”

I didn’t imagine people would call a plant with a device “adorable”. This showed me how simple tech can create meaning to achieve a new level of human interaction that wasn’t possible before. My Plantemoji was not the first – a lot of technological products have generated this level of interactivity before, and some of them have played an important role in modern life too.

Technology can add more aspects to our life

Plantemoji reminded me with another example how connected sensors sometimes add more value in community, like Apple Watch. My friends regularly share their sports and walking data with each other, and challenge themselves to break the record. These watches are devices with sensors that can detect movement, but this data acquires more meaning once it is shared between people. This social aspect of Apple Watches encourages people to act upon the data and change their life routine.

Another important example of connected technologies is smart plugs. They are becoming more and more used these days. I have noticed this in our lab at CASA, for example, where we have an MQTT feed for the electrical consumption for a lot of devices.

A recent tweet from @djdunc after we moved to UCL East showing how many smart plugs we have!

In light of the possibility of having blackouts during winter in the UK, some people proposed to use connected electrical devices to help people in controlling their devices in peak times and make them aware of how a behaviour change can benefit the whole community. These examples can clearly show the socio-technical role for connected environments, and this is only the beginning.