André Bourgeois asks, what role do connected devices play in helping us understand the world around us?

This is a question I had the privilege to spend the last five weeks exploring as part of the first module in my Master’s degree – CASA0014: Connected Environments. Throughout this module, my colleagues and I stripped back a few layers of the spaces we live in to discover and understand some of the underlying infrastructure that helps to facilitate our daily lives. We learned about the building blocks of IoT (The Internet of Things), the role it plays throughout the built and natural environments, how it can help us better understand and interact with these environments, and – most importantly – how to build our own connected devices. If this sounds like a lot for someone whose technical background consists of a dozen unfinished and forgotten online courses, you’re right, but that’s exactly what I was hoping for.

This course was roughly split between theory and practice. In lectures, we discussed connected devices and connected sensor systems, as well as the broader socio-technical impact of IoT. Many of the conversations I’ve had with people inside and outside of the classroom revolved around ethics. It’s definitely a hot topic within the IoT community, especially when looking into the development of intelligent devices in urban spaces. The truth is this technology already exists. It’s all around us. Ethical, informed, and consent-based usage will only come from a sound understanding of their design, and impacts. Technology is only good to the end that it benefits the people around it, so maintaining a human-centred approach to the development of these technologies has been a focal-point throughout the course.

Our increasingly connected world is creating new resources, data that is physically located in time and space, and gradually altering the experience of daily life – affecting social behaviour by changing how we perceive and interact with the world. Initially, these technologies manifest in a very pronounced way. However, they soon fade into the background as people adapt to their new environments. They quickly become the norm. People struggle to remember how they lived without them. One example of this always comes to mind. I vividly remember a conversation I had with my mom a few years ago.

“How do you even know where you’re going, what if you get lost?”

“Mom, I have Google Maps, as long as I have a signal, I’m never lost. I don’t think I’ve ever been lost once.”

Now, living in London, Google Maps facilitates more of my commute time than ever before. It does this so well because it’s connected. Google Maps knows the bus routes, it knows knows the tube schedule, it knows when there’s a delay, it can tell me how many Santander bicycles are at the station by my flat, it can compare ride sharing services so I can find the best deal, it knows how long all of these commute options will take me, and it always helps me get to where I need to go in the exact way I want to get there. I know that I’m exchanging my information for this convenience, I know that I’m dependent on Google Maps for my commute, and I’m okay with that. I think it’s important that people inside and outside of the IoT industry develop an understanding of the information they’re sharing and the ways in which their interactions with the world are changing. In this way, they can make informed decisions on their participation in these systems even as these technologies fade into the back of their minds. To accomplish this, I believe public and private organizations need to be more explicit with their attempts at gaining citizen consent, and providing a tangible look at what’s going on just beyond your phone screen.

Now, living in London, Google Maps facilitates more of my commute time than ever before. It does this so well because it’s connected. Google Maps knows the bus routes, it knows knows the tube schedule, it knows when there’s a delay, it can tell me how many Santander bicycles are at the station by my flat, it can compare ride sharing services so I can find the best deal, it knows how long all of these commute options will take me, and it always helps me get to where I need to go in the exact way I want to get there. I know that I’m exchanging my information for this convenience, I know that I’m dependent on Google Maps for my commute, and I’m okay with that. I think it’s important that people inside and outside of the IoT industry develop an understanding of the information they’re sharing and the ways in which their interactions with the world are changing. In this way, they can make informed decisions on their participation in these systems even as these technologies fade into the back of their minds. To accomplish this, I believe public and private organizations need to be more explicit with their attempts at gaining citizen consent, and providing a tangible look at what’s going on just beyond your phone screen.

What’s more unnerving, the thought that your social media apps are listening to your conversations, or the fact that they already have so many data points on you that they know what you’re talking about without even needing to listen? That’s not a check box, it’s a contract. You probably should have read the terms and conditions, but organizations need to stop hiding behind them.

In workshops, we dived headfirst into getting our hands on the hardware and software that make IoT possible. Bridging the gap between academia and the outside world, the course followed a “Design, Build, Critique” approach to our projects allowing us to iterate and learn in a more vulnerable and organic manner. We shared constructive criticism and best practices to gain a sound technical foundation to build on for the remainder of the program. I don’t think it’s controversial to say that academia can be a bit removed from the rest of the world. It was refreshing to learn in an environment that wasn’t based on midterms and final examinations and instead prepared students to operate in the world beyond their classroom.

In workshops, we dived headfirst into getting our hands on the hardware and software that make IoT possible. Bridging the gap between academia and the outside world, the course followed a “Design, Build, Critique” approach to our projects allowing us to iterate and learn in a more vulnerable and organic manner. We shared constructive criticism and best practices to gain a sound technical foundation to build on for the remainder of the program. I don’t think it’s controversial to say that academia can be a bit removed from the rest of the world. It was refreshing to learn in an environment that wasn’t based on midterms and final examinations and instead prepared students to operate in the world beyond their classroom.

I believe the accessibility of this course to people from non-technical backgrounds is also a huge advantage for both current and potential students, as well as the IoT industry as a whole. With its hands-on philosophy and effective information design, it’s helping to make technology accessible to the previously non-technical. More than that, it’s creating room at the table in an industry that will be leading the development of our future cities – allowing people from a variety of different backgrounds to find space in an industry they might not have felt at home in before.

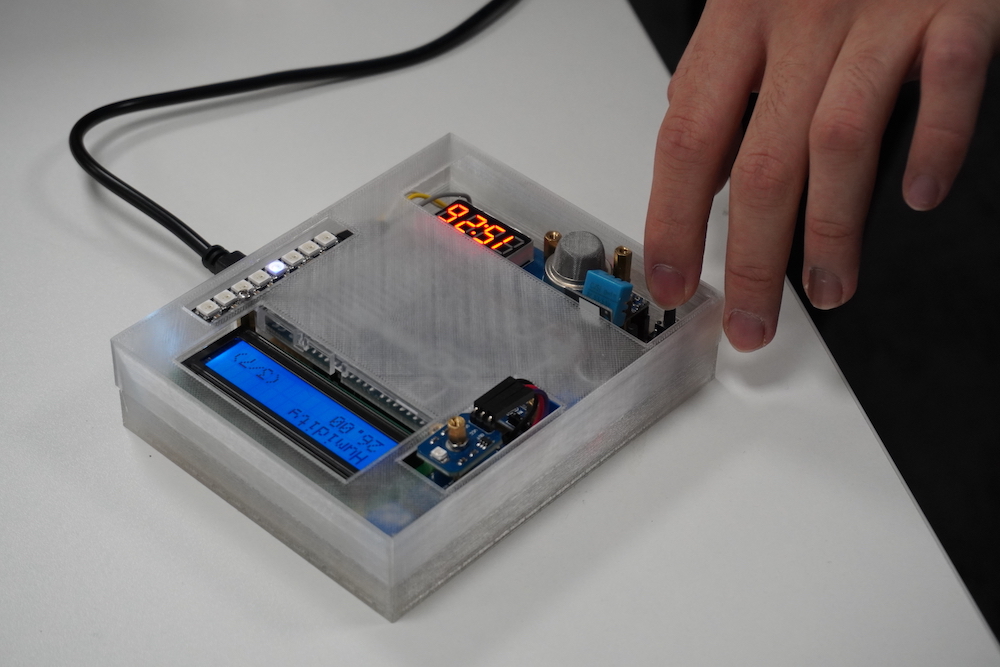

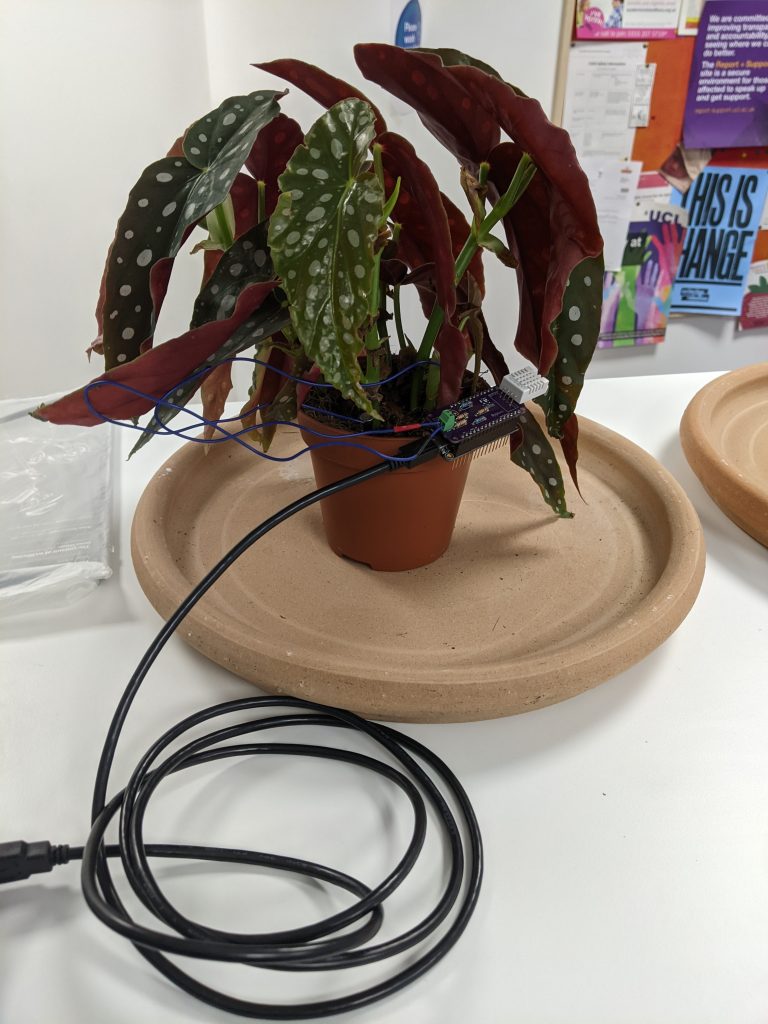

The actual projects we worked on throughout the term have provided us with a broad look at what is possible in a connected world. Throughout the term, my colleagues and I went from making an LED blink to building fully functional plant monitors. Both of these examples served to inform our understanding of, and interactions with, the world around us.

Taking a human-centered approach to our final project, the plant monitor was designed in a way that would facilitate the goals of potential plant parents. They probably want to keep their plants alive and as healthy as possible. This requires specific information about their plants’ growing environment, and it would be convenient to have that information recorded and tracked over time to uncover trends and insights. The connected devices we built accomplished this by intaking temperature, humidity, and soil moisture data and transmitting it to a database hosted on a raspberry pi. Once the information is there, plant parents are able to track and visualize their plant data and accurately inform the care of their plant. One drawback of this approach and our design is that it’s not a holistic picture of what the plant needs and some parts are subject to erosion which will negatively affect their ability to provide accurate measurements. If someone were to rely too much on this device while also not understanding its underlying technology, it may negatively affect their plant’s health in the long term. Reasonable adjustments or even iterations can be made for and on our current build to remedy any shortcomings. However, this is only possible with an understanding of the technology itself and the parts of our world that it facilitates an interaction with – in this case, the plant.

Taking a human-centered approach to our final project, the plant monitor was designed in a way that would facilitate the goals of potential plant parents. They probably want to keep their plants alive and as healthy as possible. This requires specific information about their plants’ growing environment, and it would be convenient to have that information recorded and tracked over time to uncover trends and insights. The connected devices we built accomplished this by intaking temperature, humidity, and soil moisture data and transmitting it to a database hosted on a raspberry pi. Once the information is there, plant parents are able to track and visualize their plant data and accurately inform the care of their plant. One drawback of this approach and our design is that it’s not a holistic picture of what the plant needs and some parts are subject to erosion which will negatively affect their ability to provide accurate measurements. If someone were to rely too much on this device while also not understanding its underlying technology, it may negatively affect their plant’s health in the long term. Reasonable adjustments or even iterations can be made for and on our current build to remedy any shortcomings. However, this is only possible with an understanding of the technology itself and the parts of our world that it facilitates an interaction with – in this case, the plant.

Not coming from a technical background, it was easy to feel a little overwhelmed at times. Nevertheless, in trusting the process and the people around me, I was slowly able to find my own tools and strategies that made this build easier. I’ve now created a foundation from which I feel comfortable moving on to new projects and continuing to explore and instrument our connected world.

So, what role do connected devices play in helping us understand the world around us? A more significant role than I once thought. Fundamentally, they act as a digital layer through which we experience and view our world. They can inform us, and positively affect our interaction with the built and natural environments, but they can also restrict or bias these interactions if we’re not careful. As these technologies advance, this digital layer will only continue to expand. In a future where our lives are experienced through a digital filter, collaborative effort must be made both by the people creating these technologies and those using them. These technologies can’t be developed in a vacuum, and they must be designed in such a way that maintains the authenticity of what they represent. Citizens must do their due diligence to understand the physical world, the digital layer, how they interact, and the impacts of these interactions.

Ultimately, this article is just the beginning to a lot of important conversations. It’s an account of my course, our projects, technology that already exists, and speculation on where this technology might go. It’s my advocacy to steer our connected environments in a direction that benefits the people that inhabit them, and to continue doing that regardless of anyone’s stance on the matter.